IDP News Issue No. 33

- Lancement du site Internet IDP français

- IDP France Goes Live

- La Bibliothèque nationale de France

- Le Musée Guimet

- De-Restauration – Restauration des manuscrits Pelliot Chinois 2547 et 2490

- Undoing Old and Doing New Conservation on Pelliot Chinois 2547 and 2490

- IDP’s Educational Activities and New Resources

- Exhibitions

- Publications françaises sur la route de la soie

French Publications on the Silk Road - Obituary: Song Jiayu 宋家钰

- IDP UK

Lancement du site Internet IDP français

IDP France Goes Live

Thierry Delcourt, Director of Manuscripts, Bibliothèque nationale de France speaking at the official launch of the IDP France website.

Le site internet français de IDP a été lancé officiellement le 29 avril 2009 lors d’un lancement presse au Musée Guimet à Paris, organisé par la Bibliothèque nationale de France et le Musée Guimet. Les présidents des deux institutions ont parlé de l’importance des collections de Dunhuang et de leur plaisir à voir les collections françaises accessibles sur le site internet IDP. Les visiteurs ont pu voir une démonstration rapide du site internet avant d’aller voir une exposition spéciale de manuscrits, de peintures, et d’archives de Dunhuang.

Pendant la semaine après le lancement presse, le site internet français a reçu plus de 1600 visites uniques, dont 1300 provenaient de toute l’Héxagone.

This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained herein.

The IDP French website was launched officially on April 29th 2009 at a press event at the Musée Guimet in Paris, co-hosted by the Bibliothèque nationale de France and the Guimet Museum. The presidents of both institutions spoke about the importance of the Dunhuang collections and their delight at seeing the French material now included in the material available on the IDP website. A brief demonstration of the website was given before the audience moved to the exhibition galleries to view a special display of Dunhuang manuscripts, paintings and archives.

In the week following the launch, the French site received over 1600 unique visits, 1300 from throughout France.

La Bibliothèque nationale de France

Visitors at the launch of IDP France had the opportunity to view manuscripts from the BnF in the Musée Guimet galleries.

L’origine de la Bibliothèque nationale de France remonte à la « Librairie » fondée au palais du Louvre par le roi Charles V, en 1368. La collection de manuscrits, reconstituée sous Charles VIII et Louis XII, en particulier à partir de collections confisquées durant les guerres d’Italie, a été considérablement augmentée à partir du règne de François Ier (1515-1547), qui institua également le premier Dépôt légal des livres imprimés. C’est Louis XIV et son ministre Colbert qui enrichirent ses collections orientales, en achetant des bibliothèques d’érudits et en envoyant des missions en Orient: Empire turc, Perse, puis, au XVIIIe siècle, Inde et Chine. Le site historique Richelieu, où sont restés les départements spécialisés après l’ouverture de la Bibliothèque François-Mitterrand, en 1996, fait l’objet d’importants travaux de rénovation. Mais les documents restent consultables.

Lors de sa mission en Asie centrale (1906-1908), Paul Pelliot arriva à l’oasis de Dunhuang, où il put explorer la grotte murée n° 17 qui conservait, malgré le passage tout récent de l’explorateur anglais Aurel Stein, une quantité extraordinaire de peintures et de manuscrits en chinois, en tibétain, en sanscrit, en sogdien, en ouïgour et même en hébreu. En trois semaines, il ouvrit entre 15 000 et 20 000 rouleaux et liasses, parmi lesquels il sélectionna notamment tous les textes en écritures non chinoises, et de nombreuses impressions xylographiques. Puis, dans les grottes 465 et 464, il exhuma des manuscrits et imprimés chinois, tibétains, ouïgours et xixia, qu’il acheta. Plus de 6 000 manuscrits et imprimés (dont certains antérieurs à 1035) entrèrent ainsi à la Bibliothèque nationale en 1910, tandis que peintures, œuvres d’art, carnets et photographies rejoignaient le musée Guimet. En complément, sa très riche bibliothèque sinologique (plus de 30 000 volumes modernes) fut achetée en 1946.

Grâce à l’aide de la Fondation Mellon, la BNF a pu numériser l’intégralité des manuscrits et imprimés anciens de Dunhuang, et informatiser ou achever leurs catalogues. Avec le soutien de l’Union Européenne, et en collaboration étroite avec la British Library et le musée Guimet, la BNF a décidé d’héberger le site français de l’International Dunhuang Project, dans le but de faciliter l’accès aux documents et objets conservés en France, et de permettre au grand public et à la communauté des chercheurs du monde entier de mieux connaître une collection exceptionnelle, qui n’a pas achevé de révéler ses richesses.

The origins of the National Library of France can be traced back to the collection established in 1368 at the Louvre palace by King Charles V. The manuscript collection was developed by Charles VIII and Louis XII, notably by inclusion of collections confiscated during the Italian wars, and was significantly expanded during the reign of François I (1515-1547), who also founded the first legal deposit for printed books. Although the collection already contained some oriental manuscripts, these holdings were not really developed until Louis XIV and his minister Colbert initiated the purchase of scholarly collections, both in France and by French missions to Persia, Ottoman Turkey and eighteenth-century India and China. The historic Richelieu site, which continues to house the specialist departments following the 1996 opening of the François Mitterand site, is undergoing extensive renovation works from 2010. Documents will remain accessible throughout.

Paul Pelliot reached the Dunhuang oasis on his 1906-08 Central Asian expedition. He was able to investigate cave 17 which, despite the recent visit of the English explorer Aurel Stein, still contained an extraordinary quantity of paintings and manuscripts in Chinese, Tibetan, Sanskrit, Sogdian, Uighur, and even Hebrew. In three weeks, Pelliot viewed between 15,000 and 20,000 scrolls and other books, from which he selected all the texts written in languages other than Chinese, as well as many printed documents. Then, in caves 465 and 464, he uncovered manuscripts and printed material in Chinese, Tibetan, Uighur and Xixia, which he also purchased. Over 6,000 manuscripts and printed documents and thousands of fragments thereby entered into the collections of the National Library in 1910, while the paintings, works of art, notebooks and photography from the expedition went to the Guimet Museum. In addition, Paul Pelliot’s richly endowed sinological library, containing more than 30,000 contemporary volumes, was purchased in 1946.

Catalogues of the oriental collections (Arabic, Hebrew, Persian, Pelliot, etc.) are already online, while remaining manuscripts should all be catalogued online by 2012. In addition, a growing number of digitised manuscripts are accessible through the Gallica database and the illuminated manuscripts can be accessed through the Mandragore database.

Thanks to support from the Mellon Foundation, the BnF has been able to digitise the entire collection of manuscripts and printed documents from Dunhuang and to provide online cataloguing and search tools. With European Commission funding, the National Library of France is hosting the French site of IDP, in collaboration with the British Library and the Guimet Museum, with the aim of facilitating access to the documents and objects in the French collections, thereby enabling the wider public and the worldwide research community to discover what is an exceptionally rich collection.

Le Musée Guimet

Le musée Guimet est né du grand projet d’un industriel lyonnais, Émile Guimet (1836-1918), de créer un musée des religions de l’Égypte, de l’antiquité classique et des pays d’Asie. Au cours de ses voyages il réuni d’importantes collections, présentées à Lyon à partir de 1879, puis à Paris dans un nouveau musée, inauguré en 1889.

Ce musée accueille à partir de 1927 d’importantes collections rapportées par les grandes expéditions en Asie centrale et en Chine, comme celles de Paul Pelliot ou d’Édouard Chavannes mais également les œuvres originales du musée Indochinois du Trocadéro et tout au long des années 20 et des années 30 le dépôt de la Délégation Archéologique Française en Afghanistan.

À partir de 1945, le musée Guimet envoie au Louvre ses pièces égyptiennes et reçoit en retour l’ensemble des œuvres du département des arts asiatiques du Louvre. L’institution devient l’un des tout premiers musées d’arts de l’Asie dans le monde, sous la direction jusqu’en 1953 de René Grousset qui a succédé à Joseph Hackin. Philippe Stern, qui dirige le musée de 1954 à 1965, s’attache aux activités savantes de l’institution, à la bibliothèque et surtout aux archives photographiques. Jeannine Auboyer lui succède en 1965 et enrichit les collections dans le domaine de l’Inde classique. Une nouvelle muséologie est mise en place au cours des années 70 et Jean-François Jarrige, spécialiste de l’archéologie ancienne du sous-continent indo-pakistanais, succède en 1986 au sinologue, Vadime Elisseeff, nommé en 1982. En 1991, le musée Guimet ouvre le Panthéon bouddhique, présentant une partie des collections rapportées du Japon par Emile Guimet.

Le vaste programme de rénovation qui a pris fin en 2001, avait pour but de permettre à l’institution fondée par Emile Guimet de s’affirmer de plus en plus comme un grand centre de la connaissance des civilisations asiatiques au cœur de l’Europe. En 2008, Jacques Giès, conservateur de la section Chine Asie Centrale au musée Guimet depuis 1980 et spécialiste des arts bouddhiques et des peintures chinoises, est nommé Président de l’Établissement public.

De 1906 à 1908, le sinologue français Paul Pelliot conduit une importante mission archéologique en Asie centrale accompagné du Docteur Louis Vaillant et du photographe Charles Nouette. Il a suivit le tracé nord de la route de la soie passant par Kashi, Kuche, Tulufan et Dunhuang, plus à l’est. Les œuvres rapportées proviennent de différents sites établis tout au long de cet itinéraire. Composée de manuscrits en différentes langues anciennes, aujourd’hui à la Bibliothèque nationale de France, de peintures, sculptures et textiles, conservées au musée Guimet, cette collection est avantageusement complétée d’archives papier appartenant à Pelliot, intégrées au fonds de la bibliothèque du musée Guimet, et de photographies de la mission, conservées aux archives photographiques de cette même institution.

Le projet, coordonné par IDP, de constituer une banque de données commune à l’ensemble des organismes conservant des œuvres et des connaissances rassemblées par les archéologues européens ayant fouillé en Asie centrale au début du XXe siècle, est une extraordinaire occasion de faire connaître la collection Pelliot, si complémentaire de celles conservées dans les institutions des pays européens voisins.

The Guimet Museum was originally conceived as a museum for the religions of Egypt, classical antiquity and Asia. The idea belonged to Émile Guimet (1836-1918), an industrialist from Lyon who had assembled extensive collections during his travels. He offered his collections initially to the city of Lyon and they were transferred to Paris in 1889 when the Guimet Museum was established.

In 1927, the museum acquired large collections obtained from major expeditions to Central Asia and China, including those of Paul Pelliot and Édouard Chavannes, as well as original works from the Paris Trocadero Museum of Indochina and, throughout the 1920s and 1930s, a wealth of material from the French Archaeological Mission in Afghanistan.

After 1945 the Guimet Museum transferred its Egyptian collections to the Louvre, and in return received the Louvre’s entire collection of Asian art. The Guimet became one of the first museums of Asian art in the world, and until 1953 remained under the direction of René Grousset who had succeeded Joseph Hackin. Philippe Stern, Director of the Guimet from 1954, devoted himself to the scholarly activities of the museum, including the library and especially the photograph archives. Jeannine Auboyer succeeded him in 1965 and further enriched the collections with classical Indian art. A new era of museum management was inaugurated in the 1970s with Jean-François Jarrige, a specialist in ancient archaeology of the Indian subcontinent, succeeding sinologist Vadime Elisseeff in 1986.

The Guimet Museum opened the Buddhist Pantheon in 1991, showing some of the collections obtained in Japan by Émile Guimet. An extensive renovation programme, completed in 2001, enabled the Guimet to strengthen its role as a major European centre for knowledge of Asian civilisations. In 2008 Jacques Giès, curator of Chinese and Central Asian collections at the museum since 1980 and a specialist in Buddhist art and Chinese paintings, was appointed as Director.

From 1906 to 1908 the French sinologist Paul Pelliot undertook an important archaeological expedition to Central Asia, accompanied by the medical doctor Louis Vaillant and photographer Charles Nouette. They followed the route of the northern Silk Road, passing through Kashgar, Kucha, Turfan and Dunhuang further to the east. Objects were recovered by Pelliot from different sites along this route. The Pelliot collection includes manuscripts in several ancient languages, today held at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, as well as paintings, sculptures and textiles, held at the Guimet Museum. The collections are complemented by the archives of Paul Pelliot’s personal papers and the original photographs by Nouette, both now part of the Guimet collections.

IDP’s aim to build a database shared by all institutions holding collections and knowledge of European archaeology in early twentieth-century Central Asia, offers a rare occasion to raise awareness of the Pelliot collection and related collections held in various institutions in neighbouring European countries.

De-Restauration – Restauration des manuscrits Pelliot Chinois 2547 et 2490

Françoise Cuisance

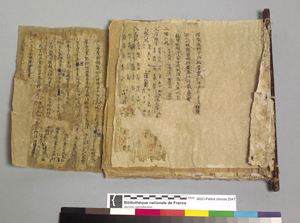

P.2547 before restoration.

Ces deux manuscrits proviennent de la désormais célèbre «grotte-bibliothèque » du site de Mogao près de Dunhuang. Ils appartiennent à l’ensemble des manuscrits acquis par Paul Pelliot, lors de sa mission en Asie centrale (1906-1908). Cet ensemble constitue le fonds Pelliot chinois de la Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF) depuis son dépôt en 1910

Ces deux pièces ont été choisies pour l’intérêt de leurs formes, reliures dites en papillon et en tourbillon, et pour l’exemple remarquable qu’elles offrent du point de vue de la restauration. Ces cas illustrent, en effet, une situation bien connue des restaurateurs d’aujourd’hui : devoir reprendre les restaurations de leurs prédécesseurs et envisager une nouvelle restauration pour une meilleure conservation des documents et lisibilité des textes, pour des raisons esthétiques mais aussi, par principe déontologique. Il est, en effet, des cas où la restauration a ‘dénaturé’ le document, comme ceux-ci, masquant sa valeur archéologique.

Ces manuscrits ont été restaurés principalement dans les années cinquante avec quelques petites additions dans les années soixante. Leurs feuillets avaient été, alors, renforcés et doublés par un papier fin collé sur leurs versos et par une mousseline de soie, sur chacune de leurs faces. Ces renforts ont exercé des tensions sur le papier des feuillets, allant jusqu’à les déformer. La réflexion pour une nouvelle restauration s’est alors imposée.

L’étude matérielle de ces documents a été réalisée, d’une part pour repérer la technique de fabrication de leurs reliures, d’autre part pour tenter de connaître la nature des matériaux qui les constituent (papier, bois, fils, pigments). Elle s’est faite en collaboration avec les laboratoires de la BnF, du Louvre, celui des Musées de France et un expert en xylologie. Les résultats sont donnés tout au long de l’exposé.

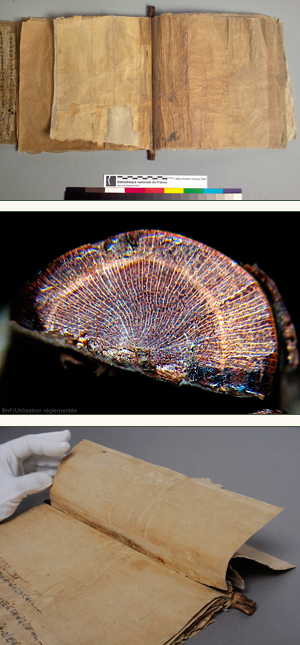

P.2547 after restoration.

L’exposé présente tout d’abord une description technique de ces manuscrits mettant en évidence les particularités de leur fabrication ainsi que les réparations ou modifications dont ils ont été l’objet, avant le XIe siècle, moment où les historiens pensent que la grotte a été murée. Concernant le Pelliot chinois 2547, nous avons pu, par ces différentes analyses et la datation au carbone 14 du bois de son bâton d’enroulement, avancer une date pour la fabrication de sa reliure. Elle daterait de la deuxième moitié du VIIIe siècle, ce qui en fait un tout premier exemple de codex relié en papillon en Chine, rejoignant ainsi les hypothèses des historiens du livre.

Après une description de l’état actuel et des restaurations précédemment faites à la BnF, le projet de restauration et la nouvelle restauration sont décrits pour chacune de ces pièces. Les restaurations des années cinquante ont été supprimées, mais les restaurations ou renforts d’origine ont été conservés pour que ces documents retrouvent un aspect proche de celui qu’ils avaient en entrant dans les collections de la BnF.

La reliure du Pelliot chinois 2547 a été conservée mais celle du Pelliot chinois 2490 ne l’a pas été. En effet, lors de la restauration précédente, cette dernière a été démontée pour réaliser le doublage de ses feuillets plus facilement puis remontée. Elle correspondait donc à une reconstitution pour laquelle nous n’avons pas d’archives et qui ne présente d’intérêt ni pour son histoire ni pour sa conservation. Les fentes et les lacunes des feuillets ont été réparées là où la cohésion des feuillets était menacée pour rendre le manuscrit de nouveau consultable.

Pour ce travail, un papier chinois, de 15g, dont la pâte est un mélange de paille et de fibres textiles, des papiers japonais de mûrier, de 17 et 20g, choisis parce qu’ils ne produisaient pas de nouvelles tensions sur les feuillets, ont été utilisés en simple ou plusieurs épaisseurs selon l’état et l’épaisseur du feuillet à restaurer.

Les deux documents seront conservés à plat, dans des boîtes de conservation adaptées aux documents. Leur numérisation et un dossier de restauration garderont la mémoire de ce travail. Ce travail collectif démontre, une nouvelle fois, l’importance d’un examen minutieux des documents avant toute intervention pour déterminer avec précision où et comment il faut agir pour mieux les conserver. Il permet aussi de mettre en évidence des éléments originaux, quelquefois ténus, qui sont autant d’indications utiles pour comprendre leur constitution et compléter l’étude de leur histoire. Françoise Cuisance est restauratrice au Départment des manuscrits de la BnF.

* Sur une proposition de Monique Cohen, anciennement Directrice du Départment des manuscrits à la BnF. Les analyses ont été réalisées avec l’accord de Thierry Delcourt, Directeur du Départment des manuscrits. Nous nous sommes appuyés sur les articles ou remarques que des spécialistes comme M. Magnin et J.-P. Drège ont fait à propos du P.2547. A la bibliothèque, H. Vetch, sinologue, et J.-M. Puyraimond, sinologue, responsable jusqu’en 2008 de la conservation des manuscrits de Dunhuang, ont été consultées au fur et à mesure de la nouvelle restauration de ces pièces.

Undoing Old and Doing New Conservation on Pelliot Chinois 2547 and 2490

Françoise Cuisance

The two manuscripts come from the Library Cave at the Mogao Caves near Dunhuang. They form part of the collection acquired by the sinologist and archaeologist Paul Pelliot during his expedition in Central Asia from 1906 to 1908. These manuscripts were entrusted to the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF) in 1910.

Conservators often need to revisit conservation undertaken by their predecessors and consider new treatments. This might be for reasons of preservation, of text legibility or aesthetic reasons, but also, as in the two examples discussed here, when twentieth-century conservation has compromised the document and concealed its archaeological value.

The two manuscripts under discussion were chosen for their two different codex forms, butterfly and whirlwind. Both are manuals with texts that would have been regularly consulted: Pelliot Chinois 2547 (P.2547, pictured opposite) is a booklet of texts to be recited on different occasions; Pelliot Chinois 2490 (P.2490, pictured above) is a table for calculating farming land. The damaged and fragmentary leaves of both manuscripts, the numerous contemporary repairs on P.2547, and the changes in binding are all evidence of their repeated use. Booklets that were easier to handle than scrolls seem to have been preferred for this kind of text.1

Description of the manuscripts

Images taken before and after restoration of P.2547, showing the early work and a detail of the tamarisk mount and, bottom, after restoration is complete.

P.2547: Entitled Zhaiwan wen 齋琬文 (Texts of purification and lament), this is a booklet of ‘texts and formulae used for various rituals’ according to its anonymous author. It is likely that the texts were composed between 647 and 788, and it is estimated that this copy was written between 728 and 7442. The manuscript was originally a scroll that was cut into fifteen bifolios and mounted on guards and so made into a booklet with butterfly binding.3 It is 280mm high, but the original length of the bifolios is unknown as they are severely damaged on the left, most-handled side opposite the roller.

The manuscript is on very even, buff mulberry paper. Before assembly, each of the folded leaves was mounted on a paper strip folded in two, called a guard, and pasted to each bifolio at the blank edge so that about a centimetre of the guard was left protruding. The mounting was necessary to make the text visible when the leaves were assembled and stitched.The guards, made of a yellow-tinted soft mulberry paper4 similar to those dyed with huangbo 黄檗 (Phellodendron amurense), were cut from a manuscript made from recycled paper that was a land register from 747 according to the date visible on one of the guards.We can therefore conjecture that the mounting was added between 762 and the occupation of this region by the Tibetans (786-848), during which time such texts were probably not used5. It is certainly an early, and possibly the first, example of butterfly binding.

The folded sheets were stacked, forming a block by pasting together all the guards. This block of guards was placed between the two halves of a small branch of tamarisk6, 10mm in diameter and 326mm long, covered in a red-brown glossy substance that is now very cracked, and is not lacquer, despite its appearance7. The guards were stitched to it using hemp thread. An old repair could be seen8. The document shows evidence of contemporary conservation using paper recycled from old manuscripts with the original text side pasted to the recto of the folio. They are made of homo-geneous mulberry paper, thicker than that of the document. and in 1954 ten pieces were removed to enable their text to be read. They were preserved separately. Also, all the folios were strengthened on their blank sides, and gaps were filled with fine paper, assuming a uniform folio size, that of the longest preserved. Then a second lining of silk gauze was placed on both faces of the bifolios, concealing the text and significantly increasing the thickness of the document from the roller.

P.2490: This is an incomplete calculation manual for the reckoning of farming areas entitled Bu shui xi jie步水畦解 (Farming Table). It bears the date 952 on the recto of the fourth folio. It is composed of six folios damaged on their left side and mounted on guards and pasted onto a roller on their right, in a kind of whirlwind booklet. The roller is made of tamarisk (see note 5).

The guards are used as a margin allowing the folios to be pasted to the roller without concealing characters. Judging from the traces of glue on the two folios without guards, it seems likely that all the folios originally had guards. In the note made before the previous restoration, it is described as a whirlwind booklet without any other detail.

The folios are made of fairly rough textile fibre paper9 with sixteen to seventeen laid lines per 4cm corresponding to the date recorded on the fourth folio10. Some thickness and opacity along one centimetre of the upper side of each folio must be related to its original formation. The folios have text on one side only, which is written inside squares drawn with thick red ink11. A few guards were cut out in this squared paper. The shape of the lines suggests that they were traced using a tool such as string that would have created lines of a distinctive shape. Bookmarks, now damaged, have been stuck to the top of each sheet; the sixth bearing the title of the manuscript. The back side of the fourth and fifth folios is used as the recto. A piece from another manuscript is partly attached by glue to the final folio and traces of glue on this suggest that there was originally another piece of paper used to make a cover, as seen on other booklets.The mounting, which is not very neat, does not seem to have been done in one sitting, but was modified in several stages. The unusual organization of the folios can be attributed to these modifications.

Past repairs, similar to P.2547, included strengthening the folios, filling gaps, and replacing missing or damaged guards. But in this instance, the folios mounted on guards were separated from the roller and from one another and then pasted back onto the roller. In 1964, the whole object was backed with modern paper. Similarly to P.2547, the linings have hardened over time and caused stress to the manuscript, deforming the folios.

This survey has shown that previous curators and conservators attempted to preserve rare texts by consolidating and fixing all fragments that could potentially be lost. They did not however consider the impact of their interventions on the original document. We now consider these interventions as excessive due to the stress they exerted on the original document, and thus need to consider new treatments.

Conservation Treatments

Initial treatment consisted of removing the linings added in 1954 and 1964 from the two manuscripts to allow the folios to be flattened and recover flexibility, making the text more legible. We hoped to return the manuscripts to the state in which they originally entered the collections of the BnF.

In particular, we decided to preserve the original binding of P.2547, but not the whirlwind binding of P.2490, the latter being a twentieth-century reconstructed binding for which we have no record, and as such holds no scholarly interest for the historian or conservator. Neither did we try to restore the folio length of these two documents, which cannot be known with accuracy. We strengthened the paper where it was weak, split or damaged, as handling was impossible or dangerous for the integrity of the texts. Pieces of paper containing text that had been added to P.2547 during contemporary conservation and had been removed in the 1950s and preserved separately were not returned to the manuscript, as we could not be sure of their original position. We did however leave contemporary conservation paper discovered in the process of reversing twentieth-century treatments.

The reversing of modern treatments has allowed us to rediscover seals and original conservation treatments that were left in situ under the modern linings as they were thought to contain no text, and so not worth removing at the time. However, one of the paper fragments bears the characters of the name of the Lingtu monastery 靈圖寺 in Dunhuang. This small piece of paper, together with three others, also bears a fragment of an unidentifiable seal and was attached to the manuscript with only a few drops of paste. These pieces came unstuck during our treatment and will be remounted on guards at their exact original position so that the fragments of text and seal will still be visible. Also, a fragment classified as Pelliot Chinois 4072 (2) was found to be a missing part of the last folio of P.2547, and will be rejoined to this manuscript.

After the folios of P.2490 were removed from the roller and treated, the paper piece attached to the sixth folio was mounted on a guard in its original position. Both manuscripts were cleaned of dust using a soft flexible goat hair brush. After checking colour stability, the modern linings were removed through gentle, progressive moistening, placing the folios one by one between two layers of Goretex cloth covered with blotters moistened with water. On account of strongly adhesive paste, we prolonged the moistening with a steam jet from an ultrasonic humidifier.

In the case of P.2547 where the binding had not been removed, we regularly controlled the moistening to prevent it from reaching either the block of guards, and making it too taut to dry without damage, or the roller, as moisture getting in the small cracks of the red-brown covering layer could stain and blacken it, causing it to expand.

The document was put on a pressboard protected from moisture with greaseproof paper, placed half-open to avoid any stress on the stitches, its roller fixed against the pressboard. The same process was followed during conservation.

For both manuscripts, after removing the silk gauze on the recto, the paper fragments were stabilised with strips of 9g Japanese paper. After a period of drying, necessary due to the fragility of some folios, the same process was undertaken on the verso to remove both silk gauze and paper linings from previous modern treatments. The removal was a slow process, although the lining paper separated completely from the folios, paper fragments and the paste. The composition of the original paste is still unknown12 but it did not mix with the paste from modern treatment. As it is very old, it has formed a film that did not disappear during lining.

The paste from modern restoration was removed from the surface of the paper with a narrow, soft flexible flat brush. In the case of P.2547, a Mylar/Melinex sheet was placed under the fragmented leaf to be moistened in order to create a provisional support for the paper fragments. At that stage, we positoned the fragments. Working from other copies of this text,13 we repositioned a badly aligned folio, and fragments or characters that could have moved during the previous lining or due to deformation of the folios. After checking the whole text, as well as the shapes of the characters, the fragments were fixed to one another, on the recto, using small 9g Japanese paper strips to conserve the verso of the folio.

We restored these documents with 17g and 20g Japanese kozo paper and 15g Chinese paper made of a mixture of straw and long textile paper fibres, chosen because they do not exert stress on the original paper.14 This conservation paper was dyed to make it look slightly different from the original paper without looking unsightly. The dye used was acrylic,15 the pigments of which do not scatter when the dyed paper is dry, even if it is remoistened.

A light, wheat starch paste was used in this treatment process; splits and tears were strengthened with narrow strips of Chinese paper; gaps were filled with Japanese paper in two or three layers corresponding to the thickness of the original folio. This was done on P.2547 on the original guards close to the mounting, allowing it to be handled again. Both manuscripts were treated where their form and the weakness of the paper might cause more tears. Paper fragments bearing characters, as described previously, were mounted on guards in their original position to allow consultation. The paper of P.2547 regained thickness after treatment as could be seen from the space between the two halves of the roller, and the paper recovered much flexibility. The folios will always retain some of the pasting from absorption when the linings were added. The mounting around the guards is still hard as it would always have been due to the original layers of paste.

Specially designed boxes were required to house these fragile documents to store them flat. For P.2547, a wedge was placed in the box to keep the roller straight. The document relies completely on a rigid and folder-shaped support, with a linen guard, so that the document can be taken out of the box without being handled. For P.2490, the folios were first placed in a folder on an acid-free board, separated with sheets of acid-free paper. The roller is stored with the manuscript. The texts will be digitized together with the individual text fragments rediscovered on backing paper. Their digitization will contribute to their preservation by reducing handling, and a conservation record will fully document these interventions.

These treatments have again shown the importance of undertaking a meticulous survey of objects to be conserved, including an analysis by specialists of their constituent materials. This enabled us to prioritise treatments for the long-term preservation of the objects, as well as to enhance those characteristics which allow us to understand their constitution and study their history.16

Notes

- 1. Jean-Pierre Drège, ‘Papillons et tourbillons’ , De Dunhuang au Japon, Études chinoises et bouddhiques offertes à Michel Soymié, Genève: 1996; Drège,, ‘Les Transformations du livre chinois (VIIIe- XIIe siècle)’, Les Trois Révolutions du livre, Imprimerie nationale, 2002. See also the IDP bookbinding web resource.

- 2. Magnin, Paul. ‘Donateurs et joueurs en l’honneur de Buddha’, De Dunhuang au Japon op. cit.: 103-138. For the text see, Paul Magnin, ‘La Sérinde, terre d’échanges, art, religion, commerce du Ier au Xe siècle’, Actes du colloque international, Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, février 1996: 79-86.

- 3. For a detailed technical description see the author’s article in Manuscripta orientalia 8.1, (March 2002): 62 -70. 4.

- 4. The first guard is made of textile paper and seems to be an original restoration, cf. Cuisance op. cit.

- 5. Hélène Vetch estimates the MS. was made after 762, taking into account the period of fifteen years as the time gap for reusing such a document: see Yamamoto Tatsuro et al. (edd.), Tun-huang and Turfan Documents Concerning Social and Economic History II. Tokyo: Tokyo Bunko, 1978-1985: 7. The C14 dating of the roller dating it to the second half of the eighth century is consistent with this (C14 dating y Pascale Richardin, Centre de recherche et de restauration des musées de France (C2RMF), Palais du Louvre, Paris). Catherine Lavier, dendrochronologist at C2RMF, says that the neat and regular finish of the longitudinal section of the split twig could only be achieved for a short time after it was detached from the tree.

- 6. Analysis by Victoria Asensi Amoros of Xylodata Company.

- 7. Jean Bleton, chemist at Orsay University-Paris 11, who is currently studying this protective covering, in collaboration with Witold Nowick, chemist, Head of Science, Laboratoires de recherche des monuments historiques (LRMH), Champs-sur-Marne.

- 8. Brigette Oger, Research Engineer, Textiles Dept., LRMH, Champs-sur-Marne.

- 9. Possibly ramie fibre according to Stéphane Bouvet, engineer at the BnF, Bussy-Saint-Georges site, who undertook fibre analysis on the documents presented in this text, using samples of approximately 2 mm2.

- 10. Fujieda, Akira, ‘The Tunhuang manuscripts: a general description’, part. 1 Zinbun 9, 1966; Drège, Jean-Pierre, ‘Papiers de Dunhuang; Essai morphologique des manuscrits chinois datés’ T’oung Pao 67(1981) 3-5, 305-360.

- 11. Made from a mixture of red ochre and a small amount of hematite. This ochre was made clearer with a mixture of calcium and magnesium double carbonate and calcium carbonate; analysis by Nathalie Buisson.

- 12. Study in progress at the BnF laboratory, Bussy-Saint-Georges site.

- 13. Pelliot Chinois 3535 and 2940.

- 14. All paper was submitted to careful scrutiny at the BnF laboratory, Bussy-Saint-Georges site by Stéphane Bouvet.

- 15. Liquitex acrylic professional art colours. See Lab. Report, Richelieu site, 25/2/97.

- 16. This work was carried out in collaboration with people mentioned in the article, as well as Jeanne-Marie Puyraimond, curator and sinologist; Cécile Sarrion, art technician and J.-M. Karchi; Philippe Salinson, Head of Photography, Reprographics Department; Patrick Bramoullé, photographer - all at BnF.

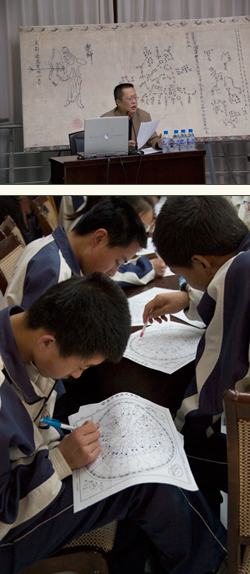

Top: Professor Luo Huaqing from the Dunhuang Academy.

Bottom: Students taking part in the workshop.

IDP’s Educational Activities and New Resources

Three IDP staff spent a week at the Dunhuang Academy (DHA) in April 2009 for the third and last educational workshop as part of the collaborative educational project funded by the Ford Foundation. The workshop was on astronomy in medieval China, continuing the theme from the London workshop held in February 2009. The DHA had made a facsimile of the Dunhuang Star Chart (British Library, Or.8210/S.3326) in the form of a frieze for students to ‘walk’ along and view. Facsimiles of other Chinese star charts were made for comparison.

Seventy 16 year-olds from a different local school to the October 2008 workshop took part. Professor Luo Huaqing gave an introductory lecture on the subject of Chinese astronomy, star charts and constellations. Students then worked in groups to identify and trace constellations. After a visit to the digitisation studio and Mogao caves, the day ended with a series of sketches written and performed in English by the students themselves covering the history and folk stories of Dunhuang. The two workshops on the same topic a few months apart in both London and Dunhuang provided useful insights into designing educational resources for Chinese and European audiences. During the visit, further digitisation training and field photography were undertaken.

Educational Resource: Buddhism

As part of the EU-funded CREA project, IDP has produced a new web resource with downloadable educational worksheets in English, French and German on the subject of Buddhism for teachers and students. The worksheets aim to offer a general introduction to the topic and can be used together or individually to introduce ideas relating to the history and basic tenets of the religion, its transmission through Asia, and its iconography and manifestation in printed documents, paintings and manuscripts from international museum and library collections. The worksheets introduce school students to Buddhism through objects in libraries and museums and their contextual information.

IDP is currently working to expand its education pages online, and this set of themed worksheets represents the first of a number of new resources that will appear on our web pages over the next year. Please look out for upcoming resources on Chinese astronomy and astrology which will appear shortly.

We welcome your feedback on our resources and hope that you find them useful in your classroom, or for your own research. Please contact Abby.Baker@bl.uk if you have any comments or suggestions, would like to order hard copies of this resource, or have an enquiry about other education services we can offer.

Exhibitions

The Silk Road

A Journey through Life and Death

La Route de la soie

Un voyage à travers la vie et la mort

The sumptious funerary costume of a corpse found in the Yingpan cemetery in the Lop Desert in western China dating to 3rd-4th centuries AD. This is currently on display in Brussels and will move to Santa Ana in March 2010.

October 23, 2009 to February 7, 2010

Musées royaux d’Art et d’Histoire

Parc du Cinquantenaire 10

B-1000 Brussels

This exhibition, jointly curated by Susan Whitfield of IDP and Zhao Gushan in China, explores the great cultural and technological exchange that took place along Eurasian trade routes in the pre-modern world and, along the way, gives an introduction to the spectacular landscapes and peoples of north-western China. The visitor is taken on both an historical and a geographical journey. This tells of the rise of the Silk Road over two thousand years ago and follows its heyday, before showing something of the Silk Road today. The visitor travels from Xi’an, the site of China’s capital city for most of its history, westward through mountain passes to deserts, great mountains and the steppe, ending in Kashgar at the western border of modern China.

Cette exposition racontera l’histoire incroyable de tous les échanges culturels et technologiques dans le monde pré-moderne. Le chemin emprunté, autant historique que géographique, emmènera le visiteur au travers de spectaculaires paysages à la découverte des peuples qui ont vécu dans le Nord-Ouest de la Chine. Il nous parlera de l’avènement de la route de la soie il y a deux mille ans et de son apogée avant de lever un coin de voile sur son visage actuel. Au cours de son périple, le visiteur suivra les routes qui, de Xi’an, ancienne capitale de Chine, mènent vers l’ouest, passant les montagnes, traversant déserts et steppes pour arriver à Kashgar, à l’extrême ouest de la Chine actuelle.

For more information see:

http://www.europalia.eu/programme/expositions/article/the-silk-road

For europalia china events see:

http://www.europalia.eu/europalia/home/?lang=en

Traveling The Silk Road: Ancient Pathway to the Modern World

November 14, 2009 to August 15, 2010

American Museum of Natural History

New York

For more information see:

http://www.amnh.org/exhibitions/silkroad/index.php

Secrets of the Silk Road

The Mystery Mummies of China

March 27 to July 25, 2010

Bowers Museum

Santa Ana CA 92706

For more information see:

http://www.bowers.org/index.php/art/exhibitions_details/35

Cultural Exchange on the Northern Silk Road

1 April 2009 to 3 January, 2010

Museen Dahlem, Berlin

Full-size copies of two of the Dunhuang cave temples can be seen at the newly opened Chinese Cultural Centre (Berlin, Tiergarten) in an exhibition on the art of Dunhuang. At the same time, the Museum of Asian Art is hosting an exhibition of artefacts from the Turfan Collection revealing the links between the oasis towns of the Northern Silk Road. The accompanying texts in the exhibition rooms will shed new light in elucidating the close ties between the various artists workshops and show the cultural exchange that occurred in terms of iconography and style.

For more information see:

http://www.smb.spk-berlin.de/smb/kalender/details.php?objID=22248&lang=en&typeId=10

The Great Game

Archaeology and Politics in the Age of Colonialism (1860-1940)

12 February to 13 June

2010

Ruhr Museum

Essen

The exhibition reveals the close links between archeology and politics in late nineteenth and early twentieth century Europe and shows the large excavations and expeditions of the age of European colonialism. Conceived in close cooperation with international partners, it showcases more than 800 artefacts from twelve different subject areas. More than sixty internationally renowned museums and institutions as well as private collectors have committed themselves to contributing works of art, some of which have never been publicly displayed before.

For more information see:

http://www.essen-fuer-das-ruhrgebiet.ruhr2010.de/en/programme/the-ruhr-mythology/the-art-of-recollection/the-great-game.html

Publications françaises sur la route de la soie

French Publications on the Silk Road

Catalogues

Catalogue des manuscrits chinois de Touen-houang Vols. I, III-VI

Bibliothèque nationale de France

Editions de la Fondation Singer-

Polignac, Ecole Française d’Extrême-Orient, Paris, 1983-2001

Also available online on IDP and BnF sites.

Les manuscrits chinois de Koutcha Fonds Pelliot de la Bibliothèque nationale de France

Eric Trombert, Guangda Zhang,

On Ikeda

Institut des hautes études chinoises

du Collège de France

Paris 2000

ISBN 2857570570 9782857570578

Inventaire des manuscrits tibétains de Touen-houang, conservés à la Bibliothèque nationale (Fonds Pelliot tibétain)

Marcelle Lalou

Paris, Librarie d’Amérique et d’Orient, 1939-

This catalogue will shortly be available online on BnF and IDP sites.

Les Arts De L’Asie Centrale: La Collection Paul Pelliot du Musée National des Arts Asiatiques—Guimet

Jacques Giès

Réunion des Musées Nationaux

Paris 1996

ISBN 0906026393 9780906026397

Les Voyageurs

Carnets de route 1906-1908

Paul Pelliot, Jérôme Ghesquière,

Francis Macouin

Les Indes savantes

Paris 2008

ISBN: 9782846541855

Missions archéologiques françaises en Chine. Photographies et itinéraires 1907-1923

Jérôme Ghesquière

Les Indes savantes

Paris 2005

ISBN: 978284654086

Mission archéologique en Asie centrale, la mission Paul Pelliot, photographies et itinéraire 1906 – 1909

Jérôme Ghesquière

Les Indes savantes

Paris (forthcoming)

Souvenirs d’un voyage dans la Tartarie, le Thibet, et la Chine pendant les années 1844, 1845 et 1846

Evariste Régis Huc

Paris : Gaume et Cie, 1878

La route de la soie dieux, guerriers et marchands

Luce Boulnois

Genève: Olizane, 2001

ISBN: 978-2880862497

Explorateurs en Asie centrale : voyageurs et aventuriers de Marco Polo à Ella Maillart

Svetlana Gorshenina

Genève : Olizane, 2003

Catalogues d’exposition

La route de la soie les arts de l’Asie centrale ancienne dans les collections publiques françaises

Grand-Palais

10 février-29 mars 1976

Éditions des musées nationaux

Paris 1976

ISBN 271180027X : 9782711800278

Sérinde, terre de Bouddha: dix siècles d’art sur la route de la soie

Monique Cohen and Jacques Giès

Galeries nationales du Grand Palais

Réunion des musées nationaux

Paris 1995

De l’Indus à l’Oxus archéologie de l’Asie centrale

Osmund Bopearachchi, Christian Landes et Christine Sachs

Association imago-musée de Lattes, 2003

ISBN: 2951667922 9782951667921

Afghanistan les trésors retrouvés collections du Musée national de Kaboul

Pierre Cambon, Jean-François Jarrige

Réunion des musées nationaux

Paris 2007

ISBN 9782711852185 2711852180

La route de la soie

Un voyage à travers la vie et la mort

Zhao Gushan and Susan Whitfield

Ed. Fonds Mercator

Brussels 2009

256 pp, 200 colour ill.

ISBN 978 90 6153 892 9

Catalogue of the exhibition currently showing in Brussels

Monographies

Les bibliothèques en Chine au temps des manuscrits : jusqu’au Xe siècle

Jean-Pierre Drège

Publications de l’Ecole française d’Extrême-Orient, v. 161

Paris 1991

ISBN 2855397618 9782855397610

De Dunhuang au Japon: études chinoises et bouddhiques offertes à Michel Soymié

Jean Pierre Drège

Genève: Droz 1996

ISBN 2600001662 9782600001663

Images de Dunhuang dessins et peintures sur papier des fonds Pelliot et Stein

Jean-Pierre Drège

Publications de l’Ecole française d’Extrême-Orient, v. 24

Paris 1999

ISBN: 2855394236 9782855394237

Cultes et monuments religieux dans l’Asie centrale préislamique

Frantz Grenet

Éd. de Centre National de la Recherche Scientif.

Paris 1987

ISBN: 222204040X 9782222040408

Histoire des marchands sogdiens

Etienne de La Vaissière

Collège de France, Institut des hautes études chinoise: Diffusion, De Boccard, deuxième édition révisée et augmentée

Paris 2004

ISBN: 2857570643

英藏法藏敦煌遺書研究按號索引

Research Bibliography on the

British and French Dunhuang

Collections

申國美、李德范編

Shen Guomei and Li Defan

National Library of China

Publishing House, Beijing 2009

RMB 1500

ISBN: 978-7-5013-3577-0

This bibliography contains more than 100,000 entries on the British and French Dunhuang collections arranged according to the institutional pressmark of collection items.

It offers scholars a convenient route to research undertaken in Chinese and Japanese on individual documents. The compliers of this bibliography, Shen Guomei and Li Defan, are librarians at the Dunhuang-Turfan Resource Center of the National Library of China.

Livres de d’intérêt général

Marco Polo et la route de la soie

Jean Pierre Drège

Paris: Gallimard, 1989

La route de la soie en 68 jours

Jean-Christophe Nothias; Serge Potier

Paris: A. Viénot, Cop. 2006

La route de la soie: d’Alexandre le grand à Marco Polo

Jacqueline Dauxois

Monaco: Rocher, 2008

Carnets D’Une Longue Marche; Nouveau Voyage D’Istanbul A Xi’An

Olivier, Bernard; Dermaut, Francois

Paris: Phébus, 2005

La route de la soie: une histoire géopolitique

Pierre Biarnès

Paris: Ellipses, 2008

Chrétiens d’orient sur la route de la soie: dans les pas des nestoriens

Sébastien de Courtois, Bertrand de Miollis

Table ronde, Paris 2007

Les Parthes et la Route de la soie

Emmanuel Choisnel

Harmattan, Paris 2004

Le grand jeu: XIXe siècle, les enjeux géopolitiques de l’Asie centrale

Jacques Piatigorsky, Jacques Sapir et al

Autrement, Paris 2009

Other

In Quest of the Buddha: a Journey on The Silk Road

Sunita Dwivedi

New Delhi: Rupa, 2009

ISBN: 9788129115218

China: A Search for its Soul.

Leaves from a Beijing Diary

Poonam Surie

New Delhi: Konark, 2009

ISBN: 81-220-0767-8

Obituary: Song Jiayu 宋家钰

The sudden death of Song Jiayu on 21 September 2009, in Beijing, is a tragic loss, not just for his family and friends but for the whole field of Chinese history, from Dunhuang studies to the Qing.

Born in Chengdu in 1934, Song Jiayu graduated in 1959 from the History Department, Peking University. In the same year he joined the Institute of History, the Chinese Academy of Sciences. In 1985 he became Head of the Dunhuang Research Team in the Institute in what was by then the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences where he spent the rest of his working life.

One of his greatest achievements was the pioneering publication of Dunhuang Manuscripts in British Collections (1990-1995). He had come to the British Library in 1987 with Zhang Gong, another Dunhuang specialist. They had intended simply to collate and correct copies of the secular manuscripts from Dunhuang made from microfilm for publication in China. They soon realized that their plan would not work as the quality of the originals was such that microfilm copies were often almost illegible. It was typical of Song Jiayu, who always approached problems directly, that he immediately raised the question of co-operation. Loyal to his roots, he negotiated with Sichuan People’s Publishing House to produce what eventually became a 14-volume set. The book won prizes in China for its elegant production and it set the standard for subsequent facsimile series.

Song Jiayu enjoyed the cut and thrust of negotiation and always did things his own way. Ever keen to help the Library, I remember some odd moments when he was determined to help us acquire, at the lowest possible price, facsimiles of the stone-carved Buddhist texts from Shijingshan which seemed to involve him in a lot of delightful bargaining and furious bicycle-riding all over Beijing.

Beth McKillop and I, in particular, have very fond memories of Song Jiayu who knew our children when they were small, who loved to laugh which made some of the difficult moments easier, who was fascinated by people and history, who was sometimes incomprehensible on the phone early on Sunday mornings when he couldn’t wait to impart information, who loved to entertain us to huge Sichuan meals, always happy with anyone who liked spicy food and who would do anything for us.

Frances Wood

IDP UK

People

Katherine Haine from Sutton High School spent two weeks at IDP UK as work experience, involving data checking and working on a web resource.

IDP welcomed Lü Ai, Zhao Liang and Sheng Yanhai from the Dunhuang Academy, for internships of between two and five months from July 2009.

Lu Ai was funded by the Dunhuang Culture Fund and during his stay in London kept a blog and took many photographs and video footage in IDP, some of which will be shown on Dunhuang TV.

Zhao Liang and Sheng Yanhai are both funded by the World Collections Programme. Zhao Liang helped with imaging, XML mark-up and writing educational resources on work at the DHA. Sheng Yanhai, IDP photographer, arrived in late November and will be helping IDP with imaging and photography.

In July 2009, Yu Jianjun and Hu Xingjun from the Xinjiang Institute of Archaeology visited IDP London for a week thanks to a grant from the Sino-British Fellowship Trust. During their stay, as well as visiting other Central Asian collections in London, they reviewed the modern photographs and video footage taken during the 2008 field trip to Xinjiang.

Xinjiang Photographs Online

More than 800 photographs taken during the IDP field trip to the southern Silk Road in collaboration with the Xinjiang Institute of Archaeology in November 2008 are now available on the IDP website. The new photographs are of archaeological sites including Shikchin, Miran, Endere, Rawak, Aksipil, Mazar Tagh, Melikawat, and Subashi. These modern photographs can be viewed alongside historical photographs taken by Aurel Stein over a century ago allowing the user to see the changes that have occurred to the site over a hundred years. The photographs can be viewed by searching by photograph and archaeological site in the advanced search on the IDP website. To see only the most recent images, add Holding Institute=‘International Dunhuang Project’ to the advanced search. Video footage of each site visited on the field trip will also soon be available on the website along with Google Earth layers.

Digitisation

Over the last few months, over 2500 images of historical photographs of Central Asian expeditions were added to the IDP database and website by the Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. Since April 2009, over 4000 images have been added to the UK IDP database including Sanskrit, Khotanese and Tibetan material.

Conservation Conference

Apologies to all those of you who signed up for the IDP Conservation Conference in Paris, 2009. Because of the restoration work at the BnF in Paris and staff commitments, it was decided it was best to postpone the conference to a more convenient time. As soon as a new date is decided we will mail out details.

Collaboration

n May 2009 Philippe Forêt and Jan Romgard of Nottingham University visited the British Library to discuss collaboration between IDP and the various collections of Sven Hedin material in Sweden. Staff from IDP UK will travel to Stockholm in January 2010 to pursue discussions further.

IDP in 2010–2012

The 15-month IDP-CREA project finished in late summer 2009 and IDP-UK is currently planning its programme for the next three years.

Among the highlights in 2010 will be the launch of the IDP website in Korea, online palaeographical resources resulting from the Leverhulme Project, completion of the digitisation of the Sanskrit fragments in the British Library, and making Stein’s expedition reports available online linked to the database records. It is also hoped to start a collaboration with Sweden (see above) and the Geographical Society in Florence, as well as incorporating items from collections in the USA and Canada.

Work has recently started on a major update of the IDP database and website. The latter will concentrate on enhacing the search function and the educational resources.

As ever, IDP NEEDS YOUR HELP to continue its work. We continue to spend a large amount of effort in fundraising and, although we continue to be successful in applications for specific projects, we struggle to find funds for basic core work, including all the technical support, conservation and digitisation. Please remember with festivals coming up that we have a Sponsor a Sutra gift scheme. Joining our regular Supporters Scheme enables us to raise funds for ongoing work but one-off donations are also very welcome. You can find more via our funding page. Our overheads are covered by the British Library and so your donation goes directly to our core work.